Driving through the Finish Line: The Fight for Suffrage on Wheels

The fight to secure the voting rights for American women had been ongoing for about 90 years when, on April 6, 1916, two women climbed into a Saxon Roadster, a small two-seat car, named “The Golden Flier” to push the movement to the finish line. Armed with a typewriter, a fireless cooker, a hand sewing machine, and a black cat named Saxon, Alice Snitjer Burke, and Nell Richardson gave speeches and debated suffrage skeptics in numerous American cities over five months. This and other efforts pushed automobiles to the spotlight of the suffrage movement. Automobiles provided quick and efficient travel for cross-country campaigning and became mobile podiums for the cause. The convenience of automobiles quickly became a national symbol for the suffrage movement. The article Driving the Disenfranchised—The Automobile’s Role in Women’s Suffrage by the Frick Pittsburgh museum stated “Female drivers challenged the notion that women ought to remain sequestered in the home. By the 1920s automobiles were a dominant cultural emblem of women’s modernity, independence, and mobility.”

The History of Female Suffrage

The exact beginning of the suffrage movement can’t be pinpointed as it was a continuous effort that spanned over decades. However, women’s effort to gain the right to vote can be traced back to the establishment of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. That same year, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John Adams to ask him to “remember the ladies”. She wanted women to have more rights under the new American government, yet her husband responded that “[The American People] know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.” During that time, many Americans believed that women’s value to society was in raising a family and establishing good morals, not participating in politics.

When Elizabeth Cady Stanton, an active participant in the fight for women’s rights, went to the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London, she met Lucretia Mott, a founder of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Despite the groundbreaking nature of this convention, men ultimately concluded that women should be barred from participating in the WASC. Mott and Stanton, undeterred, then planned to hold their convention about women’s rights upon their return home. The resulting Women’s Rights Convention, which took place in 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, was the first major event in the history of the suffrage movement. The Declaration of Sentiments was established at this convention, which outlined the expected rights of American Women regarding women’s equality in politics, family, education, jobs, religion, and morals. This grand gesture helped the women’s rights movement gain more supporters and momentum, eventually sparking constitutional change on the topic of voting rights. In 1866 and 1870, the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to slaves, and the 15th Amendment, which granted voting rights to African Americans, were added to the Constitution, again igniting the fight for suffrage.

Automobiles and Suffrage

In 1869, the National Woman Suffrage Association was founded by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. At this time, there was a deeply rooted cultural belief that men were superior to women. People believed that giving women the right to vote posed a threat to male powers and overthrowing the domestic role of a woman would disrupt the societal order. Many women joined the argument against suffrage, stating that women were too illiterate and ignorant to vote; some women even started their anti-suffrage groups. Furthermore, this sexism extended to automobiles, as women were not perceived to be capable of driving cars because they were delicate. Men thought that women should be restricted to cleaner and slower electric cars which were capable of traveling only 50 miles. Many suffragists did not support the idea of female drivers going out to campaign either—it was too controversial. Yet women still competed in organized races, volunteered for motor service during World War I, and drove cars to rally support for women’s suffrage. For these women, cars were not only a mode of transportation but also a means for changing their identity. Cars granted them physical freedom—they meant women could drive wherever they wanted while also pushing against negative stereotypes.

The spectacle of women traveling on their own inspired The National Woman Suffrage Association to use automobiles as the central symbol of the movement. Suffragists drove across their states collecting signatures and photographing each other changing tires, pictures which eventually made their way into newspapers. And these all eventually built up the journey of Alice and Nell in their Golden Flier.

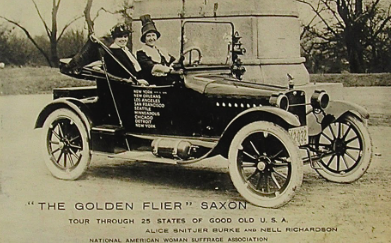

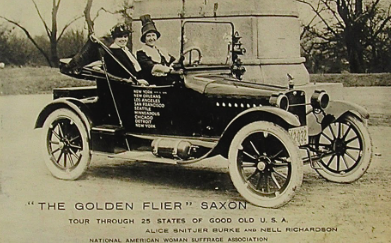

The Golden Flier

In the article “The Suffragist Saffron Saxon,” Jeryl Schriever describes the start of Alice Snitjer Burke and Nell Richardson’s trip. “Car packed, the women were ready. On Thursday, April 6, 1916, in New York City, their Saxon was christened ‘Golden Flyer’ by Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National Suffrage Association.” During their journey, they stopped to give speeches, attend gatherings, and recruited supporters for their cause. It was an impressive feat considering that the roads were barely paved and were graded with gravel. The Golden Flier often broke down because of these rough conditions.

When questioned about her ability to manage a car, Alice answered, “yes, I can run this machine without any help and without getting all messy. I’ve brought one of those clown bag suits which just let my feet and hands through. This is my working suit. It’s of deep pink linen. You can see it a mile, particularly when I stand up beside the car.” When audiences questioned her about the strange choice of bringing a sewing machine and typewriter on the trip, she said, “if any anti-suffragist down in Texas makes remarks about suffrage destroying women’s feminine talents, it will be Miss Richardson’s cue to get out the sewing machine and run off an apron while the crowd waits. If, on the other hand, he says women have no brains, she will pull out the typewriter and write him a poem.”

Richardson and Burke’s odyssey lasted for 178 days through over 10,000 miles with stops in 125 cities, including New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Minneapolis, Chicago, Detroit, and other small towns. One of their original goals was to recruit supporters to add womens’ suffrage to the party platforms in the 1916 presidential election. Although they were not able to achieve this goal, their journey attracted national attention to the suffrage movement and helped it to reach its ultimate goal in attaining the right for women to vote

The suffragists’ efforts all paid off in 1920 when the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was approved, and women were finally granted voting rights. Serving as a mobile platform for speeches and a symbol for women’s strength and intelligence, automobiles helped the suffrage movement to achieve its goal by providing efficient campaigns to gather national attention and support towards the cause. Undoubtedly, had played an important role in the American women’s suffrage movement as both a national symbol and an efficient way to reach more people.